PSA: This isn’t the shortest newsletter you’ll ever read, and it contains links to reviews and discussions you may like to explore, so consider making yourself a beverage and finding a comfy, quiet place to read before you go any further.

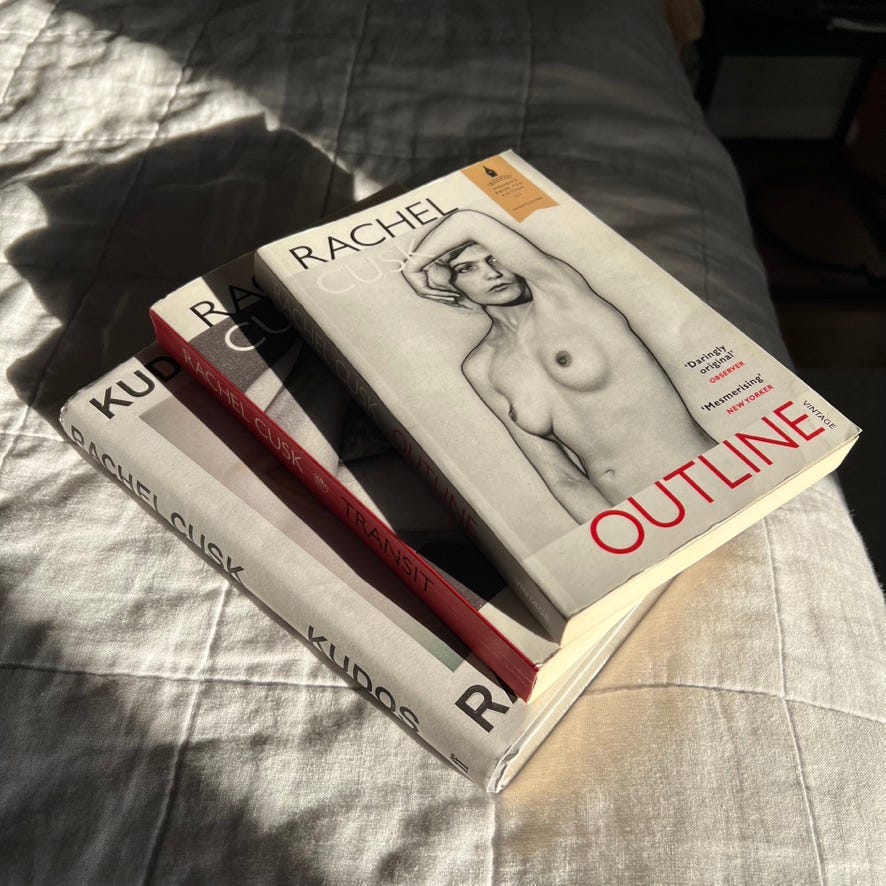

Why are we reading Outline (2014), Transit (2016) and Kudos (2018) for book club?

Outline was shortlisted for the Folio Prize, the Bailey Women’s Prize for Fiction, and the Goldsmiths Prize when it was published in 2014. It was also hailed that year in two separate Guardian reviews as “a stellar accomplishment,” (by James Lasdun) and “a triumph of attitude and daring,” in which “every single word is earned, precisely tuned, enthralling,” (by Kate Kellaway). Meanwhile, Heidi Julavits was full of praise in her review in The New York Times:

Spend much time with [Outline] and you’ll become convinced [Cusk] is one of the smartest writers alive.

Transit and Kudos completed the trilogy and garnered enormous critical respect for their Canadian-born British author Rachel Cusk. While there is of course the odd dissenting voice, most criticism seems to be couched in admiration. So I think it’s fair to say the trilogy is essential reading if you’re curious about subverting expectations or experimenting with form, or curious about the human experience in general.

Still, I only learnt of its existence a few years ago, and it’s taken those few years for the buzz to finally cut through the busy-ness of my life, and the daunting length of my TBR queue. Having borrowed these copies, I felt compelled to bump them up the list, and I’m so glad I did. If I’d bought them, I might have spent another few years eyeing them off on my bookshelf before diving in.

What is the Outline trilogy about?

Outline, Transit and Kudos are essentially a string of conversations their narrator Faye has with strangers, relatives, and friends she encounters over a period of roughly a decade. (This time-frame is not made explicit, but it feels like around ten years, based on what we learn of her sons and their progression through school.)

At the outset, Faye’s marriage has broken down and her sons are with their father while she travels to Athens to teach a creative writing course. On the plane, Faye sits beside a man and listens as he talks about his life—his marriages, his parents, their lives, his children. This is the first of the many encounters we will witness over the course of the trilogy. The rest of the action is neatly summarised by Josie Mitchell in her 2018 article in the Los Angeles Review of Books (an article that also touches on Cusk’s other books):

The trilogy [begins] with Outline, in which Faye, a writer, boards a plane to Athens. In Transit, released in 2016, Faye wanders familiar routes of London. In the final instalment, Faye travels once again, negotiating the air conditioned rooms and hot streets of an unnamed European city.

To elaborate a bit, Faye also teaches writing, goes sailing as a guest on a yacht, appears at literary festivals and events, attends dinner parties and publicity interviews, moves to London, renovates an apartment, encounters an old love interest and a new one, and ultimately remarries, though you only learn of this because an interviewer happens to mention in Kudos that she heard about it. I don’t feel that I’m giving away a spoiler by mentioning this, because Faye’s character arc is essentially incidental. It does exist, but it’s delivered with the lightest touch and its function is primarily to facilitate Faye’s encounters with people, including writers and moderators at literary festivals, fellow travellers, friends from her past, her cousin and his new wife plus some friends and their children, builders renovating Cusk’s London apartment, neighbours, publishers, and a second man on a plane.

In anyone else’s hands, this could easily make for a loose and tedious reading experience. But in Cusk’s careful, restrained and precise delivery, the observations, insights and imagery are riveting, revealing preoccupations that range from the mundane to the philosophical. They are seldom shared in the form of direct speech. Instead, they are filtered through the cool, exacting intelligence of Faye herself. Like this reported observation made by ‘a man called Eduardo’, who is speaking to Faye in a hotel lobby during a literary event, about the city in which the event is taking place:

[Jacarandas] were a feature of the landscape there, running in great tall columns along the boulevards and avenues and decorating the many famous squares. Yet it was only for the merest couple of weeks that they burst into flower, producing great ethereal clouds of luminous violet clusters, which moved in the breezes almost in the manner of water or indeed of music, as though the pretty purple flowers were the individual notes that in chorus formed a rippling body of sound. (Kudos, p169)

Faye is the ultimate writer-observer, listening, absorbing, and occasionally asking strategic questions to draw more details out of each speaker or to help them to see things in new ways (though she appears largely indifferent as to whether they do or not). While she never seems to judge them, her cool detachment affords her both objectivity and, sometimes, disdain.

Meanwhile, as noted above, Faye’s own life fades into the background, just a quiet through-line connecting the disparate stories she absorbs. The events on her personal and professional trajectory never quite form a pattern or conform to traditional ideas of story arc or meaningful character growth. Still, while she barely if ever talks about herself, her personality is an unmistakable presence. This comes across in the quality of the attention she gives to others, the responses she provides, and the questions she asks.

In a 2015 article in the Sydney Review of Books, Mereille Juchau reflects on the psychological scope of Outline:

Its rhythmic, associative, looping episodes contain a series of portraits of the mind at work understanding itself.

The trilogy is considered a work of autofiction because, like Cusk, Faye is a writer, mother, and divorcee (though Cusk has daughters while Faye has sons). As the novels unfold, Faye’s sons are either with their father, waiting for her at home or calling her on the phone, whether to get directions to school or to ask for her help with various crises and conflicts. These interactions take place exclusively on the phone and usually while the boys are in a state of a distress Faye can’t alleviate because she’s not there. These moments are quite bracing to read. Faye has given her sons so much freedom (perhaps in order to carve out her own), it comes close to neglect. And yet they always manage to resolve their issues themselves while on the phone with her. In effect, they literally and figuratively learn to sort out their issues and find their own way as the story progresses. This is interesting in its own right, but also because Cusk’s memoir A Life’s Work: On Becoming a Mother (2001) was so divisive.

Questions of Plot, Narrative Tension and Momentum

If we understand literary fiction to prioritise ideas and craft over plot and structure, then these books are at the extreme Literary end of the genre continuum. Instead of plot and narrative arcs, the heavy lifting when it comes to reader engagement is done through deft characterisation, vivid imagery and thought-provoking observations.

I’m currently working on a Creative Writing workshop about Narrative Tension, focusing on how, as writers, we use structure, character and plot to build tension. In a nutshell, I’ll be talking about how we plant curiosity seeds to pull readers along, how we create characters people care about, and how we build suspense by continually raising stakes and withholding outcomes or revelations for as long as possible. But after reading these novels, I’ll also be talking about the kind of Narrative Tension that exists in defiance of these storytelling ‘rules’, as we see in Cusk’s trilogy. Because while Cusk says she does not believe in suspense, there is nonetheless a sense of momentum that keeps you reading, which opens up space for a different understanding of how to build Narrative Tension in storytelling.

I think in these books, the tension comes down to simply wanting more. More beautiful writing, more musings, more insights and images that cause you to put the book down for a moment in order to absorb and digest what you’ve just read. More confessions and unexpectedly deep interactions between characters. And considering how many of our real-life encounters in ordinary life are shallow, skimming along on the surface of things, perhaps the Outline trilogy answers a wish within us for more meaningful, reflective, in-depth encounters with the people we meet.

Also, if suspense can be created by withholding things from readers, perhaps there is some of that going on here too. Faye’s near-silence on matters relating to her own life is a kind of withholding, enabling her, as a narrator, to remain elusive and mysterious. This arguably creates a certain charisma that’s difficult to resist.

My reading experience, as a writer:

I found Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy both inspiring and intimidating, because her sentence-level skill is so fine and precise, and her exploration of human experiences is so elaborate and thoughtful.

While I was not especially moved or engaged on an emotional level, I was captivated by the trilogy’s layers of psychological, philosophical and aesthetic resonance. For example, in the following passage, I loved the way Cusk uses one broad brushstroke (highlighted) to create such a fine image:

We had paused at a traffic light on a busy intersection and were waiting to cross the road. There was no shade, and the air shimmered over the throbbing traffic while the sun pounded unrelentingly on our heads amid the noise. On the other side of the road stood an avenue of great trees like purple clouds in whose grove-like dimness human figures were discernible. People strolled or sat on benches amid the dark trunks and beneath the densely patterned foliage, whose depths of light and shade grew more intricate the more I looked. (Kudos, p213)

At times during the reading process, I had to stop and put the book down for a minute because my brain felt saturated with images or ideas and I wanted to let them settle. If ever I resisted this need for a pause, I found myself reading subsequent passages over and over without being able to digest them. This leads me to suspect that these pauses were not just a choice, allowing myself a slow engagement with the text, but were actually a necessary part of the process, for me. In that sense, I wouldn’t call the books easy reading. But that might just be me and my capacity for concentration at the moment. Either way, the work was worth it.

I also found the Outline trilogy to be an engrossing masterclass in characterisation, as a storytelling skill. All the characters Faye encounters come vividly to life through their mannerisms, reactions, clothes, and the things they say about themselves and their lives. Which makes it intriguing that, in this 2018 interview/conversation with Alexandra Schwartz (transcribed and published in The New Yorker), Cusk says she doesn’t believe in character:

C: “[T]here’s a homogeneity afoot that I think everyone would accept in terms of our environment and how we live and how we communicate, and those things seem to be eroding the old idea of character.

S: Well, maybe it’s old for a reason. What about the subtleties of character or the subtleties of self-expression, or different personal experience?

C: I think those are shared. I’m not saying they don’t exist. I’m seeing them as more oceanic and as things that you can enter and leave in certain phases of your life that aren’t completely determined by the fact that you’re Jane and this is your life. I’m trying to see experience in a more lateral sense rather than as in this form of character. Which, as I said, I don’t actually think is how living is being done anymore. And it’s one of those ideas that hangs around in novel writing that I don’t really believe anymore.”

So now I’m ruminating over how a writer who no longer believes in ‘character’ has deftly created some of the most lingering and multi-dimensional characters I’ve come across. Is it because actions, thoughts, choices and representations are what make for memorable and meaningful literary characters rather than the more abstract notion of ‘character’ itself? Does what I just said even make sense? Please weigh in below in the comments if you have a firmer grasp of this than I do!

Finally, while we often consider a Stream-of-Consciousness style to be as close as we can get to replicating the experience of consciousness, I sometimes find that as a style it can read in a way that’s too self-conscious to feel authentic. By contrast, while the more formal style adopted by Cusk in the Outline trilogy should theoretically feel too curated and polished to give readers an experience of an unstructured internality, there is something very real about learning the details of Faye’s life so sparingly, and only through her conversations with others. Although you’d think a lack of internal reflections would limit your access to the narrator’s experiences, I think it is true that in Outline, this approach brings you very close, as a reader, to the experience of being inside someone else’s lived experience: being inside their consciousness as they navigate through life. Because arguably, within our own consciousnesses, we don’t spend all of our time reflecting on events and what they mean as they are unfolding. And our thoughts about ourselves and our lives sometimes only become apparent to us through talking (or writing) about them. Or is that just me?

Again and again, I’m encountering books and writing that remind me to slow down in my own prose, and this trilogy certainly falls within that category. I’m always afraid of boring readers with too much detail, but books like these remind me that perhaps I can afford to luxuriate just a bit more.

In closing …

There’s no shortage of thoughtful writing about Rachel Cusk and her work. For example, this article by Heide Julavits in The Cut made me wonder if I should bother adding anything at all to this conversation, while this essay by Melinda Harvey in the Sydney Review of Books is a fun and sharply observed mirroring of Outline, using narrativised conversation and characterisation to communicate ideas and critiques about the Outline trilogy itself. Very meta.

I’ve heard people question the need to read the Outline trilogy in order, to which I’d say: yes, I recommend it. While plot is not really the point, such plot elements as there are deserve to be read in order. Plus, the final image of Kudos is so potent, I think it sums up the trilogy’s themes quite brilliantly.

There is still more I’d like to say, and more examples I want to highlight—a dinner party scene, the beautiful dogs I’d like to write a whole post about, and a character’s description of a sublime burnt-out church … just to name a few—but I think I’d better show some Cuskian restraint and stop there.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this dive into Rachel Cusk’s Outline trilogy as much as I’ve enjoyed pulling it together. If you have thoughts to share, I’d really love to read them.

Thanks for joining me!

Joanna

Thanks for reading ‘Thursdays After Lunch with Joanna Morrison’! Subscribe free of charge to receive new posts and support my work.

My name is Joanna Morrison. In my debut novel, ‘The Ghost of Gracie Flynn’, three university friends are divided by a tragic death. Eighteen years on, they’re reunited, but when another body is found, the ghost of Gracie Flynn has a story to tell about the night that changed their lives forever.

What can I say, Jo! Another brilliant and articulate analysis of a literary titan I look forward to reading. So much to meditate on and absorb here. Cusk's Outline trilogy is high of my TBR list now.